In this industry, it is very easy to overlook the simplest of things, and sometimes those things can come back to bite you. Such is the case with the hydraulic design on most 6-,8- ,9- and 10-speed transmissions used today. Most of these transmissions use clutch-to-clutch shift application, which means that the need for the solenoids in charge of those clutches to time the apply and release properly is paramount for proper unit operation. In addition, units using direct-acting solenoids like the GM and Ford 8-, 9- and 10-speeds utilize a different type of hydraulic clutch control system compared to many other units today. As the units have evolved, paying attention to small details has become even more important to avoid a comeback down the road.

With that in mind, let’s take a look at a couple of areas that are becoming a common problem across many 6-,7-,8- ,9- and 10-speed vehicles. Shift flares, bumps, tie-ups, clutch slippage, and ratio DTCs are many issues a commonly worn component can create, like the solenoid accumulators/ pulse dampers. With the advent of high-frequency shift solenoid controls, manufacturers needed to equip the newer transmissions with tiny accumulators parallel to the solenoid control circuit. The solenoid accumulators/pulse dampeners are designed to smooth the pressure pulsations developed by normal solenoids operating at high frequencies. This is designed to keep valve flutter to a minimum to reduce valve and bore wear for the valves controlling the clutches. In addition, the accumulators/ pulse dampers are designed to ensure that the clutch control/shift valves will move in a steady motion improving clutch apply and release.

With that in mind, let’s take a look at a couple of areas that are becoming a common problem across many 6-,7-,8- ,9- and 10-speed vehicles. Shift flares, bumps, tie-ups, clutch slippage, and ratio DTCs are many issues a commonly worn component can create, like the solenoid accumulators/ pulse dampers. With the advent of high-frequency shift solenoid controls, manufacturers needed to equip the newer transmissions with tiny accumulators parallel to the solenoid control circuit. The solenoid accumulators/pulse dampeners are designed to smooth the pressure pulsations developed by normal solenoids operating at high frequencies. This is designed to keep valve flutter to a minimum to reduce valve and bore wear for the valves controlling the clutches. In addition, the accumulators/ pulse dampers are designed to ensure that the clutch control/shift valves will move in a steady motion improving clutch apply and release.

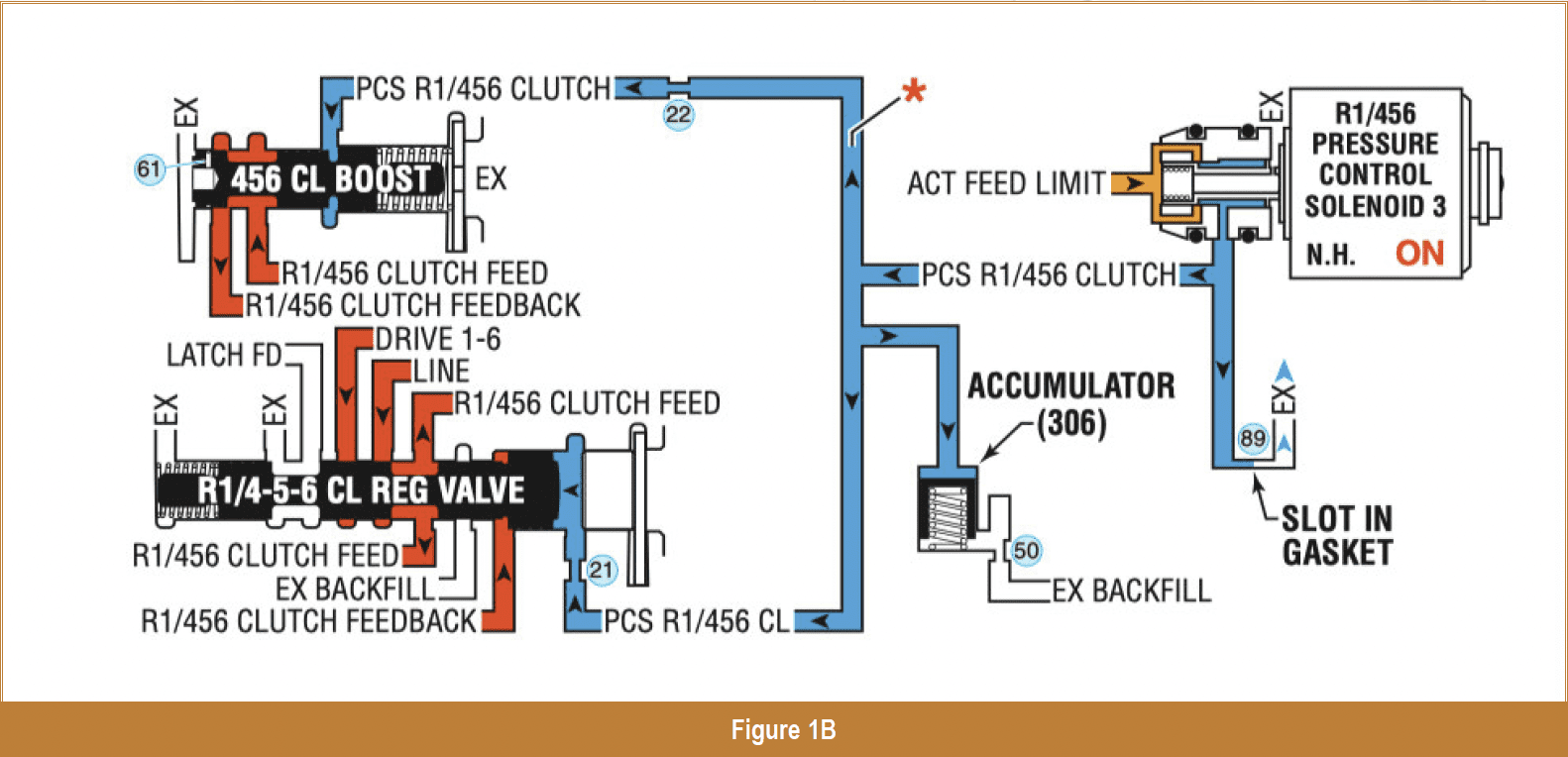

Since the accumulators/pulse dampeners are reacting to the normal operation of the solenoids, it is common to find the accumulators/ pulse dampeners with worn bores or broken springs. Worn bores can cause the control pressure for the clutch to leak, just as if you had a bad seal on the shift solenoid. If the control pressure bleeds off, the solenoid can no longer accurately control the operation of its clutch control valve leading to customer complaints (figure 1A & 1B).

It is easy to overlook the accumulators/pulse dampeners as they are small and often located in an obscure location in the valve body or support plate. Inspect the dampeners/ accumulators for bore wear like you would inspect for valve and bore wear in most transmissions today. If you find excessive wear present, either replace the valve body or the support plate that houses the dampeners/accumulators or address the issue with a repair available from the aftermarket (ream the hole and install updated/oversized accumulators).

Another issue has popped up lately regarding the 8-,9- and 10-speed GM/ Ford applications that utilize directacting solenoids. Unlike a conventional hydraulic solenoid, direct-acting solenoids do not have hydraulic pressure pulsing through the solenoid (referred to as a linear pintle solenoid by GM and a CIDAS solenoid by Ford). The solenoids control a pintle or plunger, which mechanically pushes on the clutch control valve. The clutch control valve position determines the feed pressure to the clutch. Most transmissions utilizing this technology have a solenoid and clutch control valve for each clutch. (figure2).

Another issue has popped up lately regarding the 8-,9- and 10-speed GM/ Ford applications that utilize directacting solenoids. Unlike a conventional hydraulic solenoid, direct-acting solenoids do not have hydraulic pressure pulsing through the solenoid (referred to as a linear pintle solenoid by GM and a CIDAS solenoid by Ford). The solenoids control a pintle or plunger, which mechanically pushes on the clutch control valve. The clutch control valve position determines the feed pressure to the clutch. Most transmissions utilizing this technology have a solenoid and clutch control valve for each clutch. (figure2).

A spring-loaded horseshoe clip retains each solenoid in its valve body bore. The solenoids typically operate somewhere between .1 amps to as high as 1.2 amps during normal operation. As the solenoid amperage changes, the force exerted by the solenoid pintle on the clutch control valve also changes. Solenoid amperage pushes the pintle and valve into the bore. On the other end of the clutch control valve, balance pressure is trying to push the pintle back into the solenoid. This action means that the solenoid clips get quite a workout which ultimately leads to a loss of tension. When the clips lose tension, the solenoid can start walking out of the bore, leading to clutch operational issues and solenoid bore wear in the valve body.

Here’s one way to check for a worn clip and valve body bore. When you hold the valve bodies flat, the solenoids should “not” be drooping down. If it does, inspect the bore for wear and replace the clip. In fact, consider replacing the clips during a rebuild, even if they seem ok, because it’s not if the clips will fail, but when the clips will fail. Those transmissions that see a lot of city driving, with lots of shifts, appear to have clip failure sooner than those units owned by the traveling salesman operating on the interstate that stops only long enough to refuel.

Here’s one way to check for a worn clip and valve body bore. When you hold the valve bodies flat, the solenoids should “not” be drooping down. If it does, inspect the bore for wear and replace the clip. In fact, consider replacing the clips during a rebuild, even if they seem ok, because it’s not if the clips will fail, but when the clips will fail. Those transmissions that see a lot of city driving, with lots of shifts, appear to have clip failure sooner than those units owned by the traveling salesman operating on the interstate that stops only long enough to refuel.

Well, there you have it. Something else to keep you up at night. Until next time remember, “The secret to success is to do common things uncommonly well.”