It’s no surprise that transmissions will sometimes become “the fuse” when a customer modifies or tunes an engine. The ever so popular General Motors LS engines (as well as modern LT engines) are the target of many upgrades involving long tube headers, high-flow heads, performance cams, upgraded intake manifolds, turbos and supercharging. These modifications can greatly improve the torque and horsepower output of the engine. But what about that poor 6L transmission?

In the good ol’ days, modifications to the engine would also coincide with modifications to the transmission. It seems today that matching the strength of the transmission to the output of the engine is sometimes an afterthought. For example, right now I have two vehicles in the shop where one customer is installing a Whipple Supercharger on his 5.3L engine and he has us installing a 4.10:1 AAM ring and pinion with an Eaton TrueTrac limited slip. I also have another customer (figure 1) with a 6.2L in a Camaro SS where we are installing a Texas Speed Cam (F35), LSX intake, and American Racing long tube headers. With both vehicles, I asked the customer what they plan on doing about the transmission, and they both replied, “I haven’t really thought that far. What do you suggest?” Like I said, modern transmission upgrades seem to be more of an afterthought than a package deal. Most believe that a couple tweaks with the transmission software tune is all that’s necessary to hold these transmissions together.

In the good ol’ days, modifications to the engine would also coincide with modifications to the transmission. It seems today that matching the strength of the transmission to the output of the engine is sometimes an afterthought. For example, right now I have two vehicles in the shop where one customer is installing a Whipple Supercharger on his 5.3L engine and he has us installing a 4.10:1 AAM ring and pinion with an Eaton TrueTrac limited slip. I also have another customer (figure 1) with a 6.2L in a Camaro SS where we are installing a Texas Speed Cam (F35), LSX intake, and American Racing long tube headers. With both vehicles, I asked the customer what they plan on doing about the transmission, and they both replied, “I haven’t really thought that far. What do you suggest?” Like I said, modern transmission upgrades seem to be more of an afterthought than a package deal. Most believe that a couple tweaks with the transmission software tune is all that’s necessary to hold these transmissions together.

So now you might have a 6L to rebuild and it has a destroyed torque converter clutch, or the 456 hub is snapped, maybe some pistons are cracked, or the gearset has grenaded. What if this is a bench job, and you don’t have any vehicle details? Has the engine been modified? Or has it been tuned for greater performance? Maybe the vehicle has been tuned, but what was changed and has it affected the transmission’s durability?  The purpose of this article is to show you how to check the Transmission Electro-Hydraulic Control Module (TEHCM) for a few common modifications and see if there has been any changes to torque management, pressures, shift timings, and TCC operation. The 6L units are unique in the fact that they have the TCM internal to the transmission, so we don’t even need the vehicle to check for modifications to the transmission’s software. Let’s see how this is accomplished by first looking at the necessary hardware.

The purpose of this article is to show you how to check the Transmission Electro-Hydraulic Control Module (TEHCM) for a few common modifications and see if there has been any changes to torque management, pressures, shift timings, and TCC operation. The 6L units are unique in the fact that they have the TCM internal to the transmission, so we don’t even need the vehicle to check for modifications to the transmission’s software. Let’s see how this is accomplished by first looking at the necessary hardware.

HP Tuners is by far the most common tuning software for GM vehicles. The latest MPVI3 interface costs $400 and it’s ready to use right out of the box after downloading some free software. This tool allows you to pull the “tune,” or software, from the TEHCM without any additional cost by using their VCM Editor program. After the purchase of the interface, you can view and modify the parameters, but in order to upload any tune while connected to the vehicle, you will need to pay credits. Once you purchase credits and apply them to the vehicle’s VIN, you can upload the modified calibrations an unlimited number of times.  The credits purchased and applied toward a VIN stay with the tuner’s account, so if you want to change the software on a vehicle that’s already been tuned, you will have to purchase the credits as well. The amount of credits necessary to modify the software range anywhere from 2 credits ($100 – typical chevy truck or car 2016 and earlier) to as high as 10 credits ($500 for the 2019 Vette plus a $400 TCM unlock fee). It can get pretty expensive on later model units to upload software.

The credits purchased and applied toward a VIN stay with the tuner’s account, so if you want to change the software on a vehicle that’s already been tuned, you will have to purchase the credits as well. The amount of credits necessary to modify the software range anywhere from 2 credits ($100 – typical chevy truck or car 2016 and earlier) to as high as 10 credits ($500 for the 2019 Vette plus a $400 TCM unlock fee). It can get pretty expensive on later model units to upload software.

But here’s some good news – you don’t need to purchase credits to read the vehicle’s software through the VCM Editor or to use the HPTuners’ Scanner feature. The scanner program works like a conventional scan tool, where you can read data pids and control actuators like solenoids, injectors, coils. You can also complete some diagnostic and service functions, like reset adapts, perform fast adapts, and reset fuel trims. The scanner will also read and clear diagnostic trouble codes for the transmission and engine. It’s actually a pretty comprehensive and functional scan tool. The HP Tuners VCM Editor and VCM Scanner are two separate programs and they both require the MPVI3 (or earlier) interface to operate.

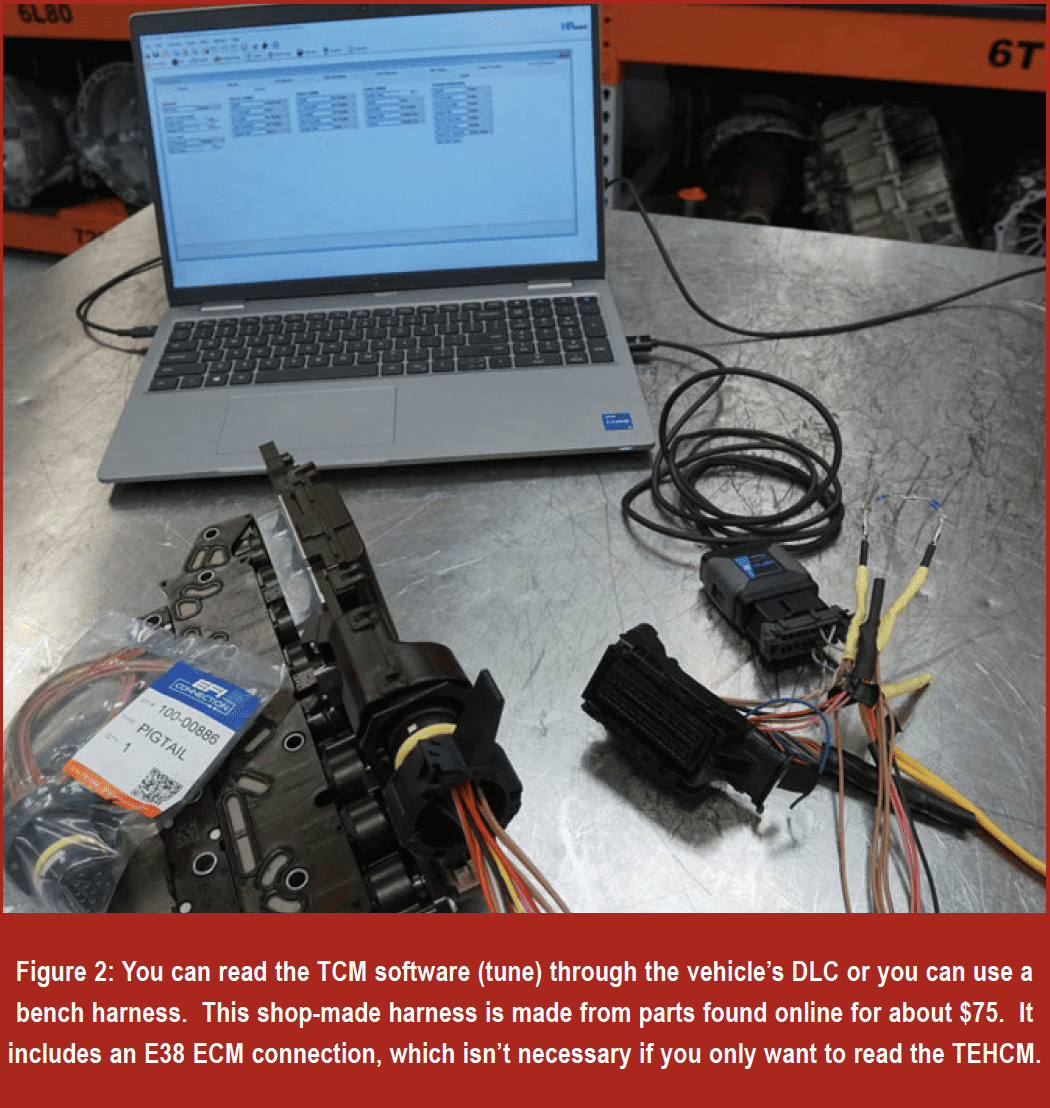

Let’s start with the VCM editor and see how it can help you determine if this transmission has been previously tuned. There are two ways to connect to the TEHCM. The first and most common is through the vehicle’s diagnostic link connector (DLC) which uses the CAN network to communicate to the vehicle’s ECM and TEHCM, and other modules. Another method is through a bench harness.  A bench harness (figure 2) is a store-bought or shop-made tool that basically includes a DLC and a harness that plugs into a 12v power source and the TEHCM. If you want to make one yourself, you can get all those connections online cheap or get them off cores. Google “6L80 TCM connector” and “OBD2 DLC connector,” and you will find connectors with pigtails for less than $75 total. I have a shop-made version and it’s ugly, but it works. When I make my next one, I’ll make the connection to the transmission much longer so I can easily hook up to a transmission in a vehicle and bypass the vehicle’s harness and CAN network. Refer to figure 3, for a simple wiring schematic to make you own bench harness.

A bench harness (figure 2) is a store-bought or shop-made tool that basically includes a DLC and a harness that plugs into a 12v power source and the TEHCM. If you want to make one yourself, you can get all those connections online cheap or get them off cores. Google “6L80 TCM connector” and “OBD2 DLC connector,” and you will find connectors with pigtails for less than $75 total. I have a shop-made version and it’s ugly, but it works. When I make my next one, I’ll make the connection to the transmission much longer so I can easily hook up to a transmission in a vehicle and bypass the vehicle’s harness and CAN network. Refer to figure 3, for a simple wiring schematic to make you own bench harness.

With the MPVI installed to the DLC, VCM Editor open, and the vehicle’s ignition ON, click on the “flash” tab and select “read vehicle.” When the dialog box opens, select “gather info.” Then, select only the TCM and click “read” as shown in figure 4. It’ll only take a short while and the TEHCM will be read and the save file dialog box will open. Go ahead and save the file with the vehicle details. You have now read the software from the TCM, and you can click on the “trans” icon to see the options available. On a side note, if you click the “edit” tab, and find the “view” option, you can select between “advanced” and “basic.” Selecting basic view will change the settings so you’ll only see options that are commonly adjusted. The advanced view shows everything that can be adjusted. In this article, I am using the advanced view.

Common modifications that can have a serious effect on transmission longevity and durability include the torque management, shift timing, shift pressures, and TCC lockup. Starting with torque management, the TEHCM tries to protect the transmission by requesting torque reduction during shifts. The torque reduction is accomplished through retarding ignition timing and reducing throttle. You can see on this scanner log for a stock 2013 Cadillac CTSV in figure 5, that for every upshift (orange trace, top graph), the spark advance drops significantly (white trace, top graph) and the throttle is reduced for a very brief amount of time (blue trace, top graph). If the tuner wants the vehicle to continue to produce high levels of torque during the shifts, they might reduce the torque management by changing the “torque factor” to something less than 1.0. Torque factor is found in the editor by selecting the “torque management” tab, then the “upshift” tab. The lower the number, the less torque reduction for the transmission during a shift.

For every vehicle I’ve checked with a stock calibration, the values are set at 1.0, like shown in figure 6. So after reading the software from your bench unit, if you find the torque factor is set to something other than 1.0, like maybe 0.7 for example, it will have less torque management than stock. An entry of 0.7 would only have about 70% of the original torque reduction, and now you know that this TEHCM has been tuned. Keep this in mind when building the transmission, knowing that more torque will transfer through these clutches and components during a shift.

For every vehicle I’ve checked with a stock calibration, the values are set at 1.0, like shown in figure 6. So after reading the software from your bench unit, if you find the torque factor is set to something other than 1.0, like maybe 0.7 for example, it will have less torque management than stock. An entry of 0.7 would only have about 70% of the original torque reduction, and now you know that this TEHCM has been tuned. Keep this in mind when building the transmission, knowing that more torque will transfer through these clutches and components during a shift.

Another torque management setting that is commonly modified is placing the “stall torque mgt” to a higher RPM. This feature enables torque management when the converter is nearing stall RPM, meaning that the impeller in the converter is turning much faster than the turbine, such as during a stall test. On hard acceleration, it’s common for the converter to approach or achieve stall speed. Under those situations, the TEHCM can request engine torque reduction if the stall RPM becomes too great. The torque converter has the greatest torque multiplication at stall speed, and stall torque management is another OE method to protect the transmission internals. But, as you can imagine, tuners will flash this feature out to improve acceleration. They do this by increasing the “enable RPM” for the stall torque management to an RPM that’s not achievable. They typically max this value out at 8192 rpm. Figure 7 shows both a 2014 Silverado (left) and a 2013 CTS-v (right) with identical stall torque management values. If these are changed to a higher RPM, the engine torque won’t be limited during WOT acceleration.

Going back to our bench unit example: if after reading the tune and seeing modifications to the torque management values, we now know that this transmission’s software has been modified and torque reduction is reduced. With this unit, the transmission internals are going to see higher levels of torque than stock, even if the engine hasn’t been modified, because these torque management settings were changed or defeated. But imagine if the engine has been modified, and the torque management was also reduced! To compensate for the additional torque, many tuners will alter the pressures and shift application times to attempt to keep clutches from slipping and overheating.

Under the “shift pressures” tab and under the “upshift” tab, you can select the different shift patterns, X, Y, and Z. These patterns are set under the “general” tab and “pattern X” is typically the normal shift pattern, and pattern Y and Z are commonly used when the vehicle not in the “D” position or it’s placed in a sport mode or tow/ haul mode. It’s common for tuners to increase the shift pressure by adding pressure to the cells found in figures 8A and 8B, which are shown at stock levels for our 6L80 and 6L90 example. Often tuners will add 20 – 50 psi to these cells to give the transmission a higher base pressure during the shifts.

Under the “shift pressures” tab and under the “upshift” tab, you can select the different shift patterns, X, Y, and Z. These patterns are set under the “general” tab and “pattern X” is typically the normal shift pattern, and pattern Y and Z are commonly used when the vehicle not in the “D” position or it’s placed in a sport mode or tow/ haul mode. It’s common for tuners to increase the shift pressure by adding pressure to the cells found in figures 8A and 8B, which are shown at stock levels for our 6L80 and 6L90 example. Often tuners will add 20 – 50 psi to these cells to give the transmission a higher base pressure during the shifts.

To work alongside with the higher shift pressures, tuners will often shorten the desired shift time by altering shift speeds through the “torque adder” tables. Torque adder is found under “shift timing,” “upshift,” then “torque adder.” Consider the torque adder values as the desired shift times, and if crisper shifts are desired, you will see these values set low. As you can see from the stock tables in figure 9, the shifts occurring at a lower engine RPM and lower engine torque hope to see shift speeds around 0.4 seconds (400ms), while shifts occurring with higher engine speeds and higher engine torque hope to see shift speeds around 0.3 seconds (300ms). If while reviewing the tune, you see torque adder values around 0.2 seconds or less, you can expect very firm shifts. Similar to the shift pressure tables in figures 8A and 8B, the “normal” torque adder table (figure 9) is typically utilized when the transmission is placed in the “D” position, and “special” is commonly used when the vehicle not in the “D” position or it’s placed in a sport mode or tow/haul mode.

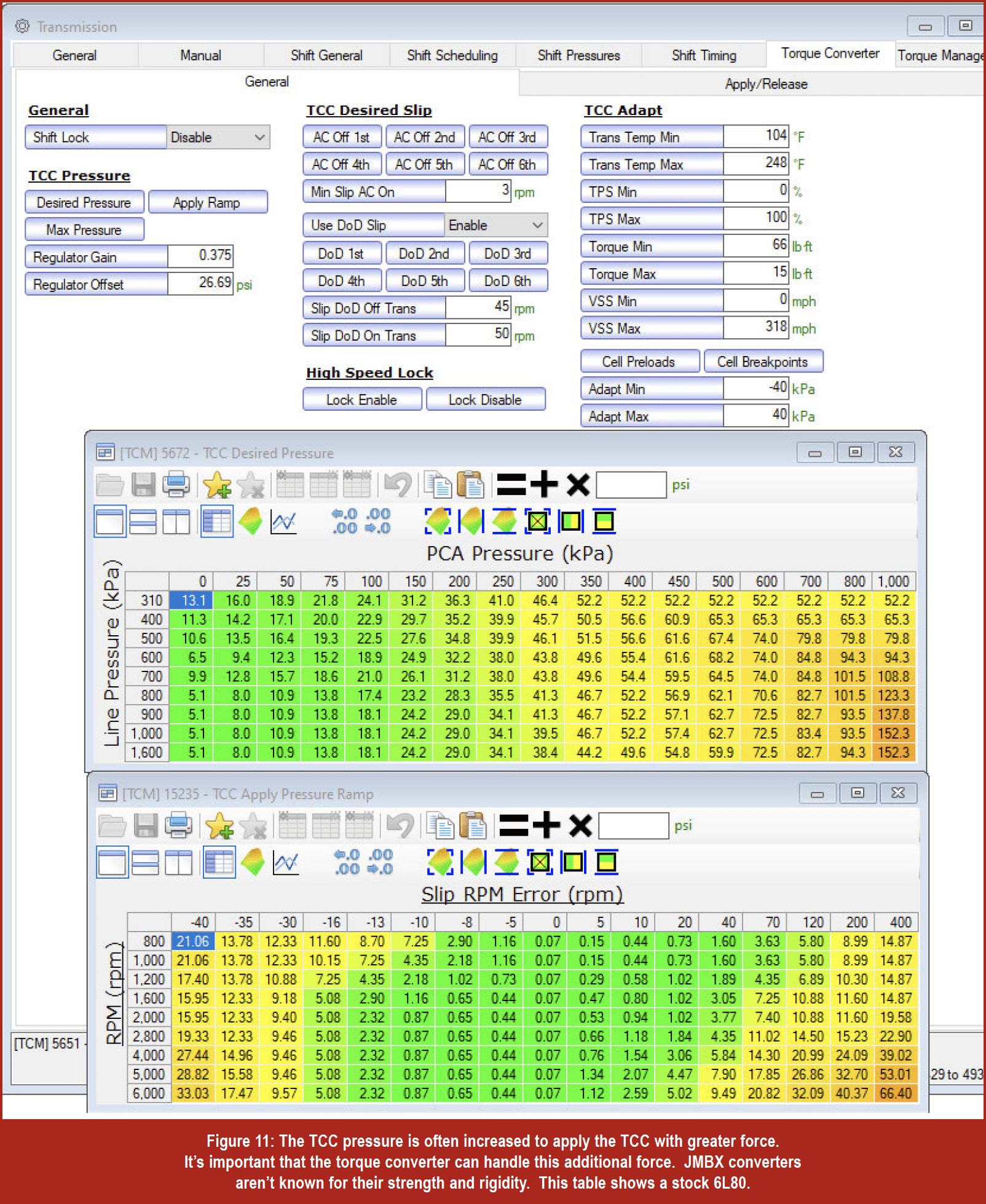

Another frequently modified section is the TCC application. Where many builders prefer to remove TCC application until higher gears, such as 4th, 5th, and 6th gear, it’s not uncommon to find tuners that apply full lockup at wide open throttle (WOT). In fact, many stock tunes also have full lockup at WOT, as can be seen in figure 11. Generally speaking, the transmission has a firmer shift when staying in lockup during the shift, but you can imagine the torque shock to the TCC if the engine has been modified with no upgrade to the torque converter. It’s a double-edged sword – there will be increase torque multiplication if the TCC is unlocked, and the parts downstream will see that increased torque, but with lockup applied, the converter clutch, dampener, and input shaft really see some serious impact.

It’s also common for tuners to increase the lockup pressure by adjusting the TCC “Desired Pressure.” The tuner can change the lockup pressure in relationship to commanded line pressure. The stock calibration attempts to keep the TCC pressure lower when line pressure increases to high levels. A tuner might increase these levels to help prevent TCC slip under heavy loads. Also, the tuner might alter the values in the “apply ramp” table to increase the pressure adjustment when slip error is detected. By adding pressure to the slip error table, the TCM will make greater pressure changes while trying to reduce TCC slip error. Keep this in mind when overhauling a transmission. If you know that the TCC pressures are going to be increased and the TCC will be applied during WOT, consider installing an upgraded converter with a billet cover and piston. When engine power is greatly increased, look into a multi-clutch setup to handle the additional torque.

It’s also common for tuners to increase the lockup pressure by adjusting the TCC “Desired Pressure.” The tuner can change the lockup pressure in relationship to commanded line pressure. The stock calibration attempts to keep the TCC pressure lower when line pressure increases to high levels. A tuner might increase these levels to help prevent TCC slip under heavy loads. Also, the tuner might alter the values in the “apply ramp” table to increase the pressure adjustment when slip error is detected. By adding pressure to the slip error table, the TCM will make greater pressure changes while trying to reduce TCC slip error. Keep this in mind when overhauling a transmission. If you know that the TCC pressures are going to be increased and the TCC will be applied during WOT, consider installing an upgraded converter with a billet cover and piston. When engine power is greatly increased, look into a multi-clutch setup to handle the additional torque.

Sometimes a little investigation goes a long way. We’ve all heard the saying, “you gotta pay to play,” and that definitely holds true in the motorsports arena. With so many of these vehicles seeing aftermarket enhancements through engine modifications, it’s important to stay informed when building 6L transmissions. The 6L transmissions give us a great advantage when compared to other units. Even without the vehicle, we can read the transmission software and see if someone’s been in there poking around. Sometimes a quick peak at the programming of the transmission control module can provide great clues to the previous life of the transmission and prepare us for what’s needed to make the unit last.