Let’s face it. They don’t make people like they used to! It seems like all aspects of life have been touched by this simple truth. Therefore, we can’t expect parts to be made as they used to. Just because a part is new doesn’t mean it will work as designed.

Let’s face it. They don’t make people like they used to! It seems like all aspects of life have been touched by this simple truth. Therefore, we can’t expect parts to be made as they used to. Just because a part is new doesn’t mean it will work as designed.

We must take the word new for its acronym meaning: Never Ever Worked, which implies that we are the Guinea pigs verifying the performance! After being burnt a few times by pretty parts in a box, my suspicion for every part I use to put in the transmissions I build has been heightened. One part I have taken for granted has come front and center in diagnosing numerous transmission operational complaints; that’s the filter.

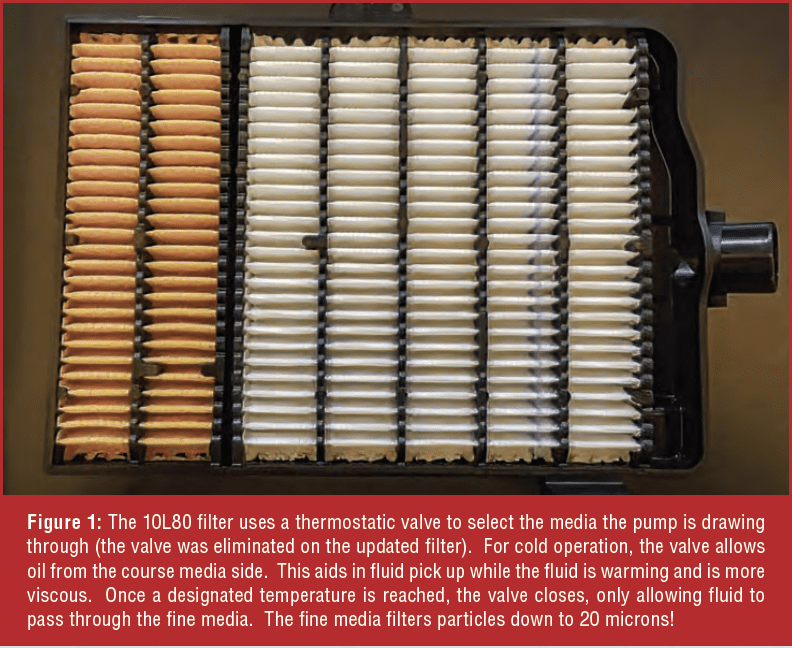

The transmission filter seems like the most challenging part to screw up, but more low-quality operations have shown us that it can be done with consistency. First, however, I must dial back my attack a few levels and give them the benefit of the doubt. Filter technology for late model applications has become a science of its own. For example, the 10L80 has a two filter elements (fine media and course media) that is controlled by an internal thermostatic valve to select which media is functioning (figure 1).  With this example in mind, we must be aware that subtle changes have been made to filters leading up to the latest technology. In this article, we will take a closer look at filters to see how we can keep from getting bit by a low-quality knock-off!

With this example in mind, we must be aware that subtle changes have been made to filters leading up to the latest technology. In this article, we will take a closer look at filters to see how we can keep from getting bit by a low-quality knock-off!

THE FUNCTION OF A FILTER

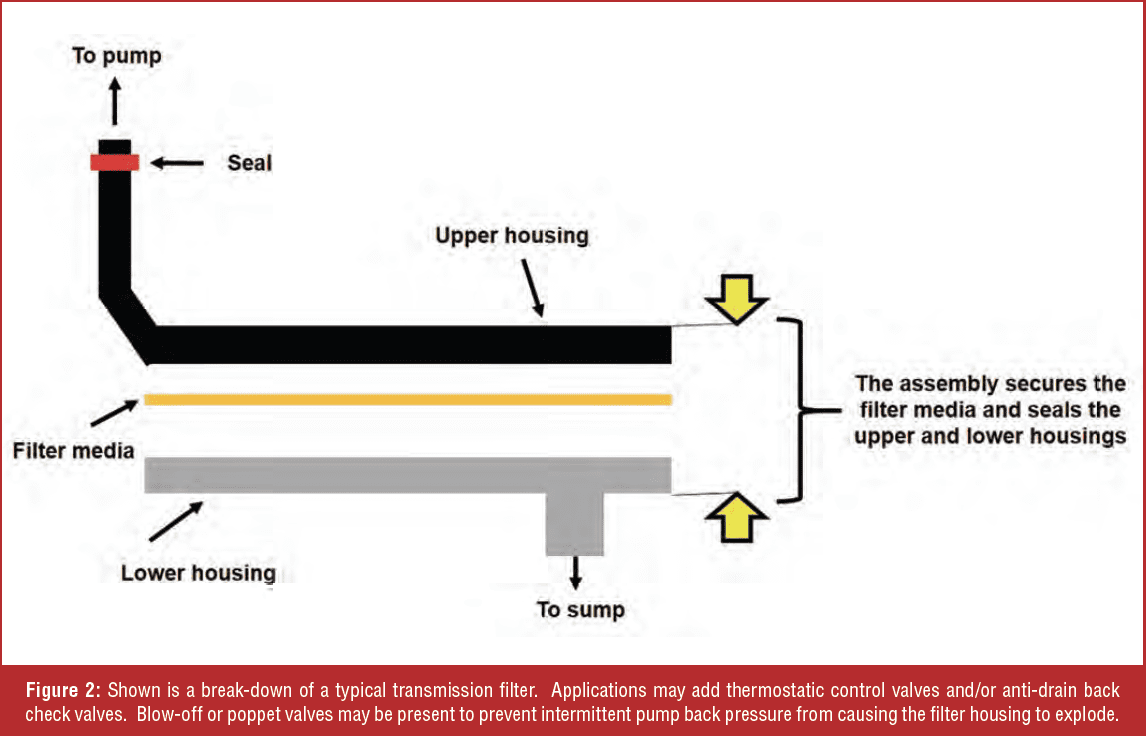

The transmission fluid filter must trap debris and contaminates, allowing clean fluid to enter the pump with minimal restriction to flow. It is designed to provide a single pathway through the filter media for fluid to enter, ensuring foreign material does not enter the pump (figure 2). The micron spacing of the filter media and the total surface area determine the level of filtration as well as the flow capacity of the filter.

The most significant restriction to flow caused by the filter occurs when the fluid is below operating temperature. An old filter also causes restriction due to trapped debris blocking the flow. Following a regular fluid and filter service regiment will ensure optimum filter performance.

The most significant restriction to flow caused by the filter occurs when the fluid is below operating temperature. An old filter also causes restriction due to trapped debris blocking the flow. Following a regular fluid and filter service regiment will ensure optimum filter performance.

WHEN THINGS GO WRONG

Filter-related issues are hard to spot because you don’t expect a filter to be a problem.

Since TH350 transmissions allowed us to replace the mesh OE filter with a Dacron element with no adverse effects, the idea of a subpar filter is foreign. We have taken the lessons from the filters of the past and applied them to the present late model units. As we mentioned earlier, filter technology has evolved into a more precise assembly. So, what kind of issues can be caused by a bad filter?

The filter is the ‘straw’ the pump uses to pick up oil from the sump and send it through the entire unit. The fluid throughput of the filter must match or exceed the throughput of the pump at all temperatures and under all load demand transitions. If the filter is unable to keep up with the pump demand or if there is an issue with its construction, the following complaints may occur:

- Whining noise under acceleration and higher engine RPM

- Fluctuating or reduced line pressure

- Falling out of gear

- Slipping on acceleration

- Performance codes

- Converter fill issues

- TCC apply issues

- Fluid aeration and overheating

- No move condition

If you suspect a cracked filter or a hole in the pick-up, you can overfill the transmission (for test purposes only) to see if your driveability symptoms disappear.

INSPECTING THE FILTER

Some filter designs require precision manufacturing materials and processes to ensure the performance meets the OEM specifications. The filter media, housing material, and assembly directly impact the end product. Always compare the filter in question with the OEM filter when in doubt. Often a visual inspection will reveal differences in appearance.

Testing the filter’s performance is impractical; however, testing its integrity is easy. Rod Palmer of Norfolk Transmissions in Norfolk, Nebraska, gave me a simple test he did before installing filters on his units.

Testing the filter’s performance is impractical; however, testing its integrity is easy. Rod Palmer of Norfolk Transmissions in Norfolk, Nebraska, gave me a simple test he did before installing filters on his units.

Using a vacuum tester, plug the inlet into the filter while applying vacuum to the pump pick-up (figure 3). Allow the vacuum reading to settle at a final value. Do not leave a full vacuum applied to the filter for an extended period. The filter housing is not designed to sustain integrity under a full vacuum. Note that the reading should not drop. If a sudden drop occurs, this indicates a crack. Leaks in the housing indicate construction issues that cause fluid pick-up and converter charge-related issues.

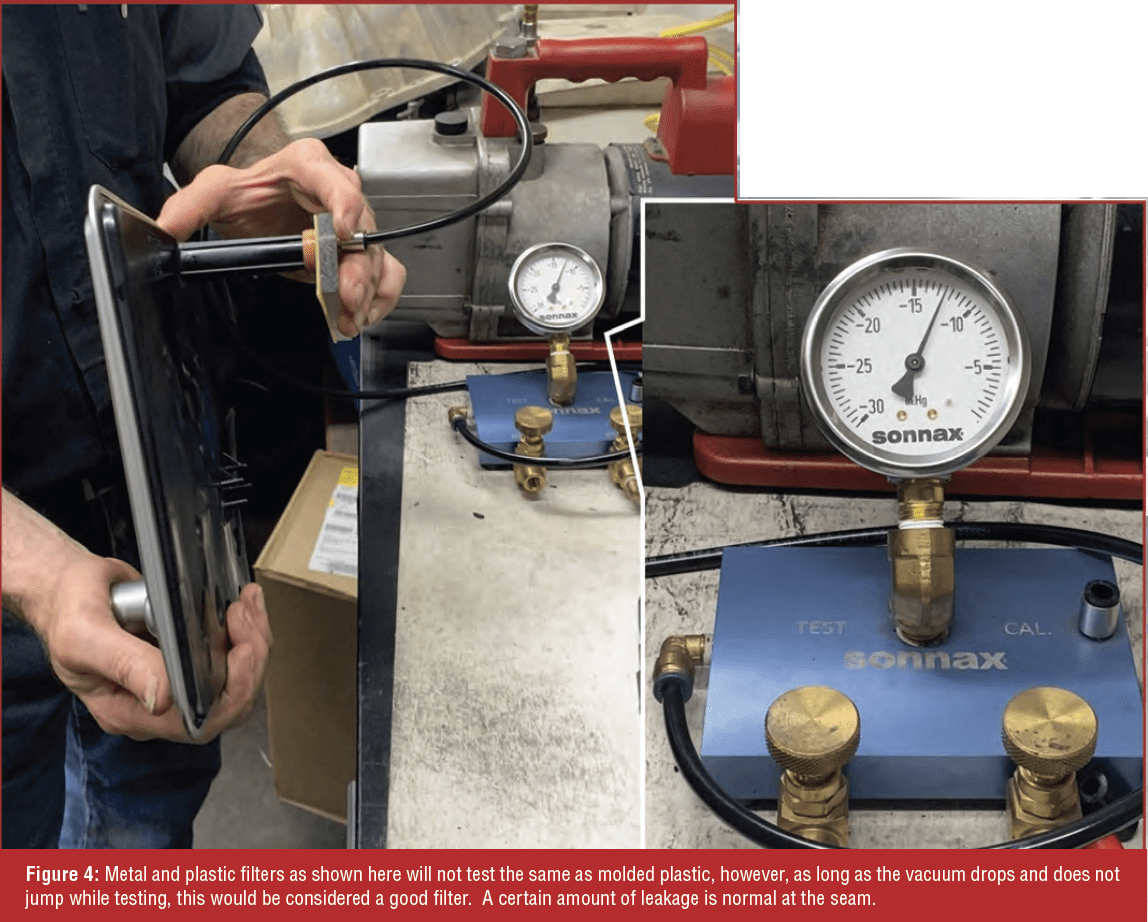

Filters constructed of metal and plastic are critical to test for sealing at the seam (figure 4). By design, these filters will not test as well as the molded plastic assemblies. The junction where the filter media is secured is where you will observe minimal leakage. There will be a certain amount of leakage, but you should not see a drop as you apply vacuum.

Filters constructed of metal and plastic are critical to test for sealing at the seam (figure 4). By design, these filters will not test as well as the molded plastic assemblies. The junction where the filter media is secured is where you will observe minimal leakage. There will be a certain amount of leakage, but you should not see a drop as you apply vacuum.

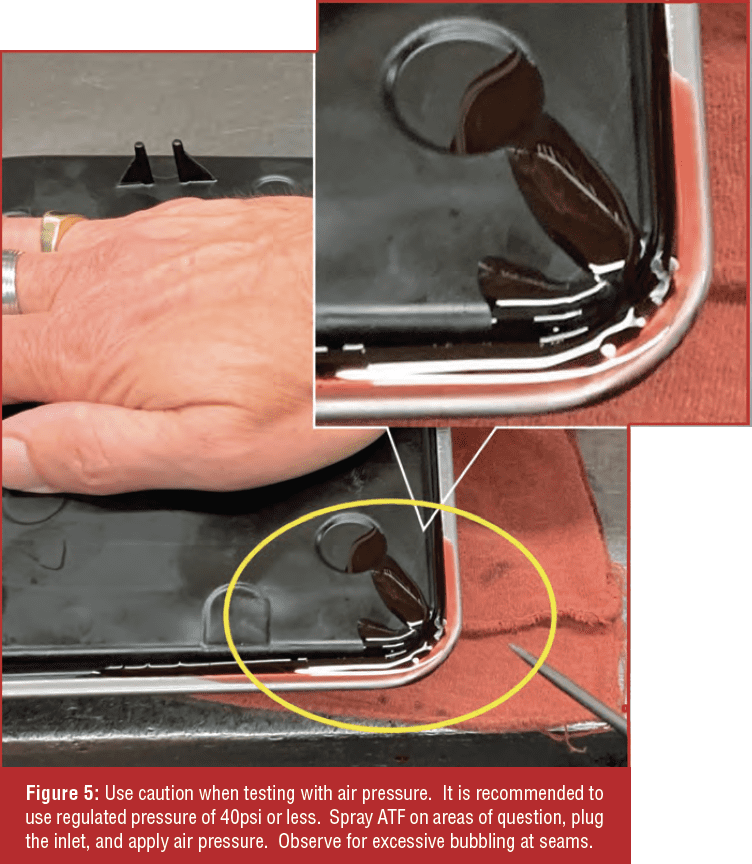

You can perform a similar test using air pressure, but you must take care not to over-pressurize the filter (figure 5). Pressure can create leaks. You can spray transmission fluid on the surfaces of the filter in question, seal the inlet, and apply air pressure (recommended no more than 40 psi). Observe for excessive bubbling on seams or other areas of concern. Note that areas not submerged in the transmission fluid sump must not leak.

Another area of concern is the filter media. Although it is out of sight, you can use an inspection camera or a bore scope to look inside (figure 6). Again, use an OEM filter for comparison. Of course, appearance does not guarantee proper function, but if it looks significantly different than the factory design, you may not wish to take a chance.

Filter media-related concerns to be aware of are as follows:

Filter media-related concerns to be aware of are as follows:

- Media becoming dislodged, causing a restriction

- Wrong micron spacing of filter media for application (too fine restricts flow; too wide allows contaminants to pass)

- Inadequate internal support for media (filter structure)

While a visual will not tell you the performance capabilities of a filter, it may alert you to observe subtle transitional performance concerns.

With supply chain issues plaguing our industry, it isn’t easy to ensure the consistency of quality parts for our transmissions. Even the most straightforward parts must be verified, so the quality of our end product is not compromised. Developing new habits for inspecting parts will help weed out defective components and allow us to deliver the goods to the customer correctly the first time!

Thanks to Rod Palmer of Norfolk Transmission, Norfolk, NE, for the technical information!